Keep it simple

‘Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication’

Leonardo da Vinci

The late, great Paul Volcker, the towering former Federal Reserve chair, said in 2009 that “the ATM has been the only useful innovation in banking for the past 20 years”. At Troy, we agree with the sentiment that most complex investment bank products are not good for customers. We deliberately eschew financial engineering and, in the battle for investment survival, our preference is for simplicity even if at times this can look unsophisticated or unfashionable.

Our purpose is as much to avoid the traps as it is to provide positive returns. The ability to make unforced errors – to buy high and sell low, which is sacrilege for those seeking to preserve and grow capital – is easier and more common than you might think. Fear and greed often cause investors to panic out at the bottom and pile in at the top. This inevitably leads to mediocre returns, at best. Our approach is the antithesis to this, leaning in and increasing risk on price weakness, as we did during the Financial Crisis and Covid, while reducing risk in periods of ebullience as at the end of 2021. We are intrigued, but not surprised, to see Warren Buffett increase his liquidity in 2024, as prospective returns from equities today look modest.

We always start with the premise that we must buy well. At a recent Troy Investment Team offsite, we reviewed our stock picking since 2001. Over the past two decades or so we have acquired 92 equities for our Multi-Asset mandate, of which 18 have lost over 10% from the initial purchase price. A hit rate of 80% is good, but there is always room for improvement. The other side of this is selling well – recognising when we have made a mistake, or when the facts have changed. We have sold an average of just over three companies a year and continue to advocate for low turnover, not no turnover. Investing in liquid shares and complementary assets provides the flexibility with which to do this.

The elephant in the room

In July we wrote about elections and our aim never to position the portfolio for a single outcome. As we approach the US presidential election on 5th November, the biggest risk is likely to be that there is no clear winner, and the outcome is disputed. Markets would certainly loathe such uncertainty and we can only hope for clarity.

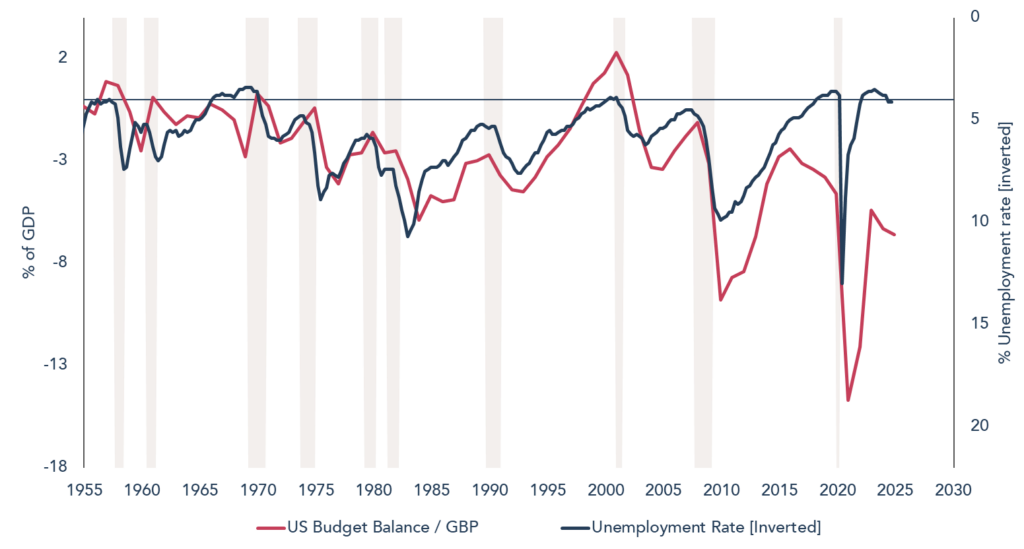

There appears, however, to be one certainty regardless of who is elected to the White House. A striking absence from both presidential candidates’ platforms is any mention of the United States’s fiscal position, despite this being clearly out of control. The fiscal deficit is running at 7% of GDP, a level more common in the depths of a recession (Figure 1).

Figure 1: US budget deficit compared to the unemployment rate

Source: Bloomberg, 30 September 2024. Past performance is not a guide to future performance

Recent unemployment figures point to the very strange economic cycle we have experienced since Covid, characterised by distortions including ‘labour hoarding’ but also the Federal Reserve and the US government prioritising labour over inflation. While many economists have expected the higher interest rates of 2022-24 to bite, employment has remained resilient thanks in part to record fiscal spending. The growing public sector, in the form of government-related employment, accounts for 59% of the increase in recent payroll data. Such fiscal largesse is likely to continue under a Harris presidency. Meanwhile, a Trump presidency promises tax cuts, with little if any cuts to spending. The deficit will grow whoever wins. But why does this matter? Stock markets seem at ease with the deteriorating fiscal maths.

A lose/lose?

Four years ago, in the world of rock-bottom yields, wags used to refer to US Treasury yields as ‘return-free risk’. They were right, as yields subsequently rose in 2022 and bond prices fell. An investor, buying a 2030 Treasury at the start of 2021, has now lost -11% of their money. The supposed risk-free returns from government bonds were anything but. Investors have exited that zero-interest rate world of the 2010s and there is today a yield for bond holders, but is it enough to compensate for the risks we see ahead?

Looking at the various scenarios, a soft landing or even ‘no landing’ will lead to minimal cuts in interest rates and perhaps the return of inflation should demand get too hot. In such circumstances yields may rise (and bond prices fall again). The debt burden at the Federal level, and its ever-rising interest cost, may once again come into focus. Closely behind social security payments, interest payments are the second largest outlay for the US government. According to Jefferies, interest payments have risen from 8.3% of government receipts in April 2022 to 18% in August 2024, the highest level since 1993. Back then however the government debt-to-GDP was 63%, versus 120% today.

What if the delayed effect of tighter monetary policy and higher interest rates leads to a hard landing and a recession? In that case, the budget deficit would soar as tax revenues fall and government spending is maintained. Either way, soft landing, no landing or recession, the fiscal deficit is becoming unsustainable and is likely to push yields higher.

As the supply of US Treasuries increases, bond investors are bound to seek greater compensation in the form of higher yields for longer-dated bonds. Lending money for a long time to a more indebted government ought to require a greater yield to reflect the associated risk. Back in the early 2000s, when disinflationary forces remained strong and interest rates were declining, we deemed long-dated government bonds to be attractive. We were happy to hold long-dated UK gilts in the form of the 3½% War Loan and 2½% Consols during this time. But these bonds were sold from the portfolios well over a decade ago. Long-term lenders to the US and UK governments today are taking on more risk for less return. We believe the repricing of this asset class is ongoing and will have implications for asset prices elsewhere. If low bond yields justified higher equity valuations, surely the opposite corollary is true? Since December 2021 the US 10-year Treasury yield has risen from 1.5% to 4.2% today. Yet valuations in the US stock market have barely fallen. Whether this is a paradox or merely a delayed reaction to the inevitable remains to be seen.

The least painful solution to the predicament of unsustainable debt levels and a rising cost of interest would be to fix long-term yields. Such yield curve control might seem unthinkable today, but it is not unprecedented. The US Treasury capped rates on long-term Treasury securities from 1942 to 1951, when debt levels were similarly stretched. After the unprecedented use of unorthodox monetary policy in the form of QE and zero rates, we cannot rule out the necessity of using this tool in extremis, if and when yields spike. This would result in the suppression of real interest rates, financial repression and debt monetisation, with dire implications for savers and bond investors.

A pig in a python

The real squeeze from higher interest rates is more obscure in the world of private equity, where leverage levels are traditionally higher than in the quoted arena. Evidence is building that all is not well in this unregulated and opaque world.

While this may not appear relevant to us, investment in private equity and private credit has grown so strongly since the Financial Crisis 15 years ago that it has the ability to affect wider asset markets. Since 2008, ‘alternatives’ have been in vogue for large asset allocators, especially endowments. These investors could see the attraction of holding assets that were not marked to market each day, thereby encouraging the view that these holdings reduced portfolio volatility. If an asset is only priced quarterly, at a level decided by a tiny subset of the investment world, then naturally such volatility is obscured. A low interest rate made fixed income investments ever-less appealing and alternatives more attractive. Another popular asset class, private credit, has filled the void left by banks retreating from lending after the Financial Crisis. The limited disclosure from private markets makes it hard for investors and regulators to assess the scale of leverage in the system, but opaqueness often results in poor behaviour in financial markets.

A recent report from Markov Processes International, A Private Equity Liquidity Squeeze, highlights an increasing reliance by US institutional investors on illiquid and alternative assets, especially private equity. The very successful Yale Model for endowments, as pioneered by the late David Swensen, was embraced after 2008 but has now arguably reached extremes. We suspect, in future, those with low exposures to alternatives will have better long-term returns.

Typically, private equity funds require endowments to commit to future investments on demand, as opportunities arise. A normal year of distributions would be enough to fund capital calls from other PE commitments, but this is not happening. According to Bain & Co there are as many as 28,000 companies globally that the PE industry would like to list, at a time when the IPO market remains lacklustre. It is true that a fall in interest rates may provide some comfort to PE sponsors and their investors but, if that coincides with an economic downturn, the outcome could be mixed. The scale of the challenge for private markets has been highlighted from within the industry itself; Scott Kleinman, Co-President of private credit specialist Apollo, in a recent speech at an industry conference said: ‘I’m here to tell you everything is not going to be OK… The types of PE returns it (the industry) enjoyed for many years, you know, up to 2022, you’re not going to see that until the pig moves through the python. And that is just the reality of where we are.’

The Markov report poses the question of how large institutions cope with an intensifying liquidity squeeze. Endowments and other fellow PE investors may need to sell their liquid assets of stocks and bonds if they are unable to unload their locked-up PE funds. Ironically then, illiquid alternatives may pose a threat, at least in the short to medium term, to liquid financial markets.

Interest rates to the rescue

The remarkable surprise in 2024 has been the low number of interest rate cuts. With seven cuts expected at the start of the year in the United States, only one 0.5% cut has been forthcoming, in September. The Bank of England has similarly cut rates only once (by 0.25% to 5%) on 1st August, with a casting vote from the Governor, Andrew Bailey.

Many market participants expect interest rate cuts to boost equity prices by lowering the cost of capital and supporting higher valuations. We take an alternative view for two reasons. Firstly, equity valuations have not fallen as the cost of capital has risen in recent years. So it seems odd to suggest that valuations should then rise as yields fall. Secondly, most market declines only happen after the first interest rate cut. This has certainly been the case for each of the past three cycles. The first Federal Reserve cuts occurred in January 2001, August 2007 and July 2019. On each of these occasions, the US stock market was trading close to its highs and subsequently fell -44%, -53%, and -25% respectively.

Close to record high equity market valuations, combined with the risk of recession and a sea of geopolitical and policy risks, mean we continue to be cautious with the equity weight in the strategy. Perhaps this time will be an exception and equities will continue to rally as yields fall. We are not holding our breath.

A pet rock

Gold bullion has continued to confound the sceptics this year. While the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times, our newspapers of financial record, have described gold as a ‘pet rock’, gold bugs have also been perplexed as higher real interest rates have failed to have their usual negative effect on the price. Western investors have sold until recently, judging by ETC (exchange traded commodity) outflows. Central banks in China, Singapore, Turkey, India, Czech Republic and Poland, among others, continue to buy. Perhaps the unsustainable US fiscal situation, described above, is being noticed. The yellow metal may once again be appreciated as the ultimate perceived safe-haven and reserve asset it always was. We have reduced our gold holdings modestly since the summer, but it remains essential portfolio insurance at circa 12% of Troy’s Multi-Asset mandate. As the American business journalist, Henry Hazlitt, once said, ‘The great merit of gold is precisely that it is scarce; that it is limited by nature; that it is costly to discover, to mine, and to process; and that it cannot be created by political fiat or caprice.’

Disclaimer

Please refer to Troy’s Glossary of Investment terms here.

The information shown relates to a mandate which is representative of, and has been managed in accordance with, Troy Asset Management Limited’s Multi-asset Strategy. This information is not intended as an invitation or an inducement to invest in the shares of the relevant fund.

Performance data provided is either calculated as net or gross of fees as specified in the relevant slide. Fees will have the effect of reducing performance. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. All references to benchmarks are for comparative purposes only. Overseas investments may be affected by movements in currency exchange rates. The value of an investment and any income from it may fall as well as rise and investors may get back less than they invested. Neither the views nor the information contained within this document constitute investment advice or an offer to invest or to provide discretionary investment management services and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision. There is no guarantee that the strategy will achieve its objective. The investment policy and process may not be suitable for all investors. If you are in any doubt about whether investment policy and process is suitable for you, please contact a professional adviser. References to specific securities are included for the purposes of illustration only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell these securities.

Although Troy Asset Management Limited considers the information included in this document to be reliable, no warranty is given as to its accuracy or completeness. The opinions expressed are expressed at the date of this document and, whilst the opinions stated are honestly held, they are not guarantees and should not be relied upon and may be subject to change without notice. Third party data is provided without warranty or liability and may belong to a third party.

Issued by Troy Asset Management Limited, 33 Davies Street, London W1K 4BP (registered in England & Wales No. 3930846). Registered office: 33 Davies Street, London W1K 4BP. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN: 195764) and registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) as an Investment Adviser (CRD: 319174). Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Any fund described in this document is neither available nor offered in the USA or to U.S. Persons.

© Troy Asset Management Ltd 2024.